|

本帖*后由 Stone654 于 2016-12-16 19:41 编辑 大师访谈:Pierre Bensusan Adam Perlmutter,翻译Stone654

2009年9月22日,Bensusan正在英国的Borneouth民谣俱乐部弹奏32年间深受其信赖的吉他:Old Lady 摄影:Paul Savine 很多出色的吉他演奏家都使用过DADGAD调弦,它的空弦音听起来是一个Dsus4和弦,可以突破传统标准调弦的桎梏。它灵活性强,适合凯尔特音乐,印度的拉格音乐,以及美国西弗吉尼亚的阿巴拉契亚音乐。英国民谣先驱Davy Graham在60年代早期广泛使用这个调弦,由于他的启蒙,一些伟大的摇滚乐手比如Jimmy Page以及Trey Anastasio也对其有所涉猎。但只有少数演奏家像Pierre Bensusan一样如此热衷于用这个调弦来作曲。到现在差不多四十年,Bensusan用这个调弦创造了一种高度融合凯尔特音乐、中东音乐,以及爵士和巴西音乐的个人曲风。 Bensusan现年53岁,他出生在阿尔及利亚的Oran,并在巴黎长大。这样的童年经历对他之后的音乐风格产生了深远的影响。和许多年轻的音乐家一样,他深受60年代民谣复兴的影响,在他发展出自己标志性的指弹技法之前,他像Woody Guthrie和Bob Dylan一样用扫弦伴唱。 Bensusan在签订他的第一份唱片合同时才17岁。一年后,他的处女专辑Près de Paris (1975)在瑞士的Montreux爵士音乐节上赢得了法国唱片大奖。自那以后,Bensusan发行了大量精心制作的专辑,内有像管弦乐般复杂迷人的吉他独奏曲。Bensusan还写了The Guitar Book这本书来解释他的唱片中每首曲子的故事和想法。 拥有温润的男中音和标志性的爵士唱法的他同样是一位有成就的歌手。不同于以往的专辑,他的新专辑Vividly收录了等量的纯器乐演奏和弹唱的乐曲。但是专辑中吉他的独奏丝毫不逊色以往,密集的和弦与非凡的走向紧紧抓着你的耳朵,竖琴般的和声与大量的对位轻轻地拨弄着你的心弦。 我们*近采访了Bensusan本人,简要地谈了他产生的影响,昙花一现的电声效果以及其它一些事情。 Q1:你早年的吉他经历是怎样的呢? A1:我十一岁那年得到了人生的第一把吉他,开始扫弦伴唱一些法国民谣和美国民歌。之后我接触到了Bert Jansch和John Renbourn这样的演奏家的作品,这令我恍然大悟:原来吉他还可以这样弹!之后我便开始学习应用对位技法的指弹演奏。 Q2:你是怎样开始使用DADGAD调弦的呢?为什么它给了你这么大的影响呢? A2:早些年我偶然发现过许多调弦,一段时间过后,我认为自己应该选择其中的一种去钻研精通。我选择了DADGAD调弦,并在1978年后只用这种调弦。(只有一个例外,Bensusan在他的作品Altiplanos中采用了标准调弦)这是一种讨人喜欢的调弦,随便弹弹都能让你兴奋上好一会。但是如果你不深入研究其中的奥秘,仅仅停留在表面功夫的话,你的作品听起来就会和所有这么做的人一样了。于是我开始认真地琢磨这个调弦,练习大量的音阶与和弦,实验不同的想法和风格。一段时间过后,我就能在这个调弦下自如地表达我的想法了。DADGAD这几个空弦音被隐藏在我的音乐之中了,现在是我在运用这个调弦,而不是受它支配。

Bensusan正在弹奏由Dave Evans制作的23弦竖琴吉他 摄影:Doatea Bensusan Q3:和我们聊聊作为你多年的主力琴的那把Lowden吧。 A3:1978年我去北爱尔兰旅游时结识了一位叫George Lowden的朋友。几个月后,我在巴黎的一家店里看到了一把Lowden,当场喜欢上了它的声音和外观。我马上给George打了一个电话,找他定制了一把桃花心背侧雪松面板的吉他。到现在差不多33年间,我是用这把琴录制了许多唱片,并给它起了Old Lay这个名字。(正式的商品名为S22)我还有一把Lowden叫New Lady,到今年才使用三年,是我的签名型号。它有云杉面板、玫瑰木背侧,与我之前的那把声音有很大的不同。它很灵敏,声音很空灵,并且十分清澈明亮。这把琴*神奇的一点就是它太顺滑了,稍不注意就可能失去控制。演奏时我必须时刻全神贯注,这是一件好事。 Q4:你说新吉他容易“失去控制”,是什么意思呢? A4:如果弹奏方式得当,你能获得一个立体的几乎完美的声音,但是如果不注意的话,你会被它过于强力的混响搞得摸不到头脑。我对能如此专注地使用这把琴演奏表示感谢,这是很正常的一件事,而且能让我的琴技精进。 Q5:你的作曲过程是怎样的呢? A5:首先,我任凭我的思维去驰骋,然后用吉他将其再现出来。开始,一首新曲子可能是我一时突发的灵感,然后在接下来的几周几个月甚至几年间,我会在不失本意的前提下丰富其内涵。技巧会歪曲你原本的创作意图,对此我格外地小心。总的来说,作曲夯实了我的基本功,为了准确表达某种意境所付出的努力拓展了我对指板的掌握程度和对乐器本身的认识。

2009年Bensusan在德国的一场演出,图为1978的那把Lowden吉他,特点是雪松面板,桃花心背侧 摄影:Schramberg Q6:这么说在作曲之初你就已经想好旋律了? A6:通常来说是这样的,开始只是存在于我脑袋中的一个完整想法,和吉他并没有关系。只有在时机合适的时候,我才会用吉他赋予它一个具体的音乐形式,用一种不失治愈效果的方法去表现。当然我也在随意把玩吉他的时候产生过许多灵感,实际情况的话应该是两者的结合吧:灵感对吉他的娓娓倾诉,寻找正确的音符。 Q7:你的风格融合了世界各地的元素。你能具体谈谈对你的影响都有哪些吗? A7:噢,种类实在是太多了。我能从阿拉伯音乐(我出生在北非)谈到凯尔特音乐,法国中部的歌曲,再一路到巴西、印度、古巴、马里以及更远的地区。我就像一块海绵,贪婪地汲取着世界各地的灵感。不是通过学习技巧和理论,而是身处当地用眼睛去观察,用耳朵去倾听。除此之外,我的音乐还受到我现在的生活以及当今世界的影响,毕竟我们不是生存在伊甸园中。感谢音乐,让我再过去四十年里走遍了全球各地,体会到了多远的地理文化。这无疑对我的作曲产生了影响。 Q8:有时候你会使用George Benson那种爵士唱腔,你是怎么开始这样演唱的呢? A8:我第一次听到Milton Nascimento(一位巴西的词曲作家)的作品时,我觉得它不但是一位伟大的歌手,而且是一位用其富有感染力的嗓音作画的画家。是他启发了我用歌喉去增强吉他的感染力,与此同时,我从George Benson那里学到了爵士唱腔,之后又受到Bobby McFerrin的启发。但是我发展的是属于我自己的风格,毕竟一味地模仿别人是没有任何意义的。

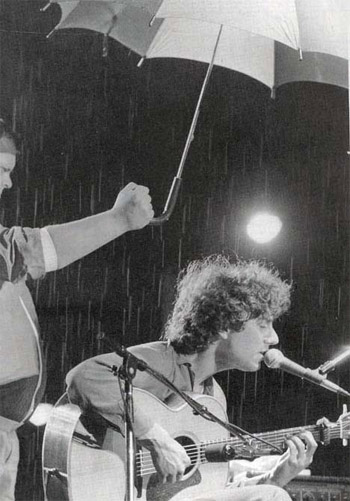

1986年魁北克音乐节上Bensusan在演奏自己的原创曲目,打伞的人是Bob Walsh 摄影:Henri Pichette Q9:80年代那会儿,你开始使用效果器创造一种丰满的音色,但后来你完全放弃了电声效果。这是为什么呢? A9:我是那种不情愿进入新领域,但一旦进入就会一直走下去的人。就像在玩具店玩耍的孩子一样,我对ping pong延迟效果感到惊奇,对超过一分钟的loop目瞪口呆——你可以一层一层往上面叠加声部。我用这种特效表演了十五年,创作的音乐也达到了极高的水准,虽然我知道有些人并不喜欢我的这种实验性作品。效果器让我感到自己很强大,但也伴随着一个风险:我开始觉得自己离不开效果器了,这令我很恐慌。于是在一次巡演前,我看了看我的设备,对它们说:“你们就乖乖地留在这吧。”接下来的演出中我只带了一把吉他和一根连接线,我试图用吉他的原声去打动听众。 开始的时候,我感觉被剥夺了效果器简直弹不下去。吉他声听起来非常小,在有些场子的音响系统中会有杂音。但我接受了这些小瑕疵,并戴着镣铐起舞。我痴迷于一些事情,比如用美妙的颤音技巧去叙说一段故事。不久之后,我意识到一场简单的演出甚至不需要音响系统,一把吉他和一个房间就已经足够。现在我巡演时只带*基本的东西:吉他,一个音量踏板,一个混响单块,两支麦克风,一个吉他支架和一个谱架,避免我忘词。就这么多东西,*占地方的就是一个电风扇。 Q10:摒弃了电声效果从根本上影响了你的演奏吗? A10:是的。效果,尤其是混响,能够掩饰吉他原本的声音,让你忘却其本来面目是什么样的。当你不插电演奏的时候,你会为其质朴的声音感到困惑,认识到想要让它发出美妙的声音着实要花费一番力气。不用电声效果之后,我发现自己更加注重双手触弦的技巧和力度变化了。我不得不在原声层面上保持演奏的精准,这也是我现在录音不戴耳机的原因,通常只在后期稍微润色修饰一下。 Q11:和我们聊聊你的*新专辑Vividly吧。 A11:上一次录音时(2001年的Intuite专辑),我没有唱歌。但这次我想让歌曲和器乐演奏平分秋色,我试图让专辑整体听起来具有一层意思,然后每首曲子自己还有一层意思。有些歌曲是与我妻子Doatea以及洛杉矶歌曲作家Nina Swan一同合作录制的,每一首我都谨慎地处理伴奏不至于和人声冲突。我想让听众一次只注意一件事,避免他们对其产生困惑。换句话来说,我把人声部分也当成和吉他同等重要的一件乐器。我很高兴别人对我说Vividly是我目前为止发行过的*好专辑。我的琴艺精进了,唱歌也比以前更好听了。*重要的是,它证明了我作为一个演奏家和音乐人的地位。 Q12:即兴演奏似乎在你的音乐中占主导地位。 A12:当我作曲时,我总是倾向于写一些那种你可以源源不断添加新灵感进去的作品。当然我会先一音不差地把之前的版本弹出来,但马上我会开始自由发挥,用手中的音符去表达自己内心的想法,跟着乐曲的指引走。我对即兴的一点看法是:有朝一日你总得把之前学过的全部知识都放下,当你经过刻苦训练所有演奏技巧都不能阻碍你的时候,忘却一切才能让你真正流畅地表达内心所想,无招胜有招。

New Lady这把吉他是Bensusan的签名款,采用阿迪朗达克云杉面板, 洪都拉斯玫瑰木背侧,马达加斯加玫瑰木琴码, 五拼枫木琴颈,乌木贴面琴头,悬铃木、玫瑰木和桃花心镶边。 摄影:George Lowden Q13:什么是即兴高手的真正秘诀呢? A13:渊博的指板知识很重要,你必须能迅速找到任何一个给定的和弦的不同位置,搞清楚它们的走向,以及多种多样的音阶和调式。有朝一日,你会下意识地演奏出美妙的旋律。音乐绝对不是理性分析与和声堆砌的产物,再绚丽的外表下面,有一个绝对可靠的抽象概念,好比地下宝藏一样吸引你的思绪、意念,乃至任何人类的感情。语言在这些面前是苍白无力的,因为如果能用话讲得清楚,那么演奏和欣赏音乐就显得多此一举了。 原文: Interview: Pierre Bensusan Adam Perlmutter January 17, 2011 A lot of great guitarists have made use of the DADGAD tuning—in which the open strings sound a Dsus4 chord—to break the constraints of concert tuning. That’s because it’s versatile and adaptable to Celtic tunes, raga, and Appalachian styles, among others. British folk pioneer Davy Graham used it extensively in the early ’60s, and in his wake great rock players like Jimmy Page and Trey Anastasio have dabbled in it, too. But few instrumentalists have made so much from it as fingerstyle legend Pierre Bensusan. For nearly four decades now, Bensusan has used the tuning to play his highly personal blend of Celtic, Middle Eastern, jazz, and Brazilian strains. The 53-year-old Bensusan was born in Oran, Algeria, and reared in Paris—an upbringing that would eventually lend a cosmopolitan sense to his music. Like many young musicians, he got caught up in the folk revival of the 1960s, strumming and singing songs in the mold of Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan, before developing his trademark fingerstyle approach. Bensusan was only 17 when he signed his first recording contract. A year later, his first album, Près de Paris (1975), won the Grand Prix du Disque at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland. Since then, Bensusan has released a handful of carefully conceived albums filled with compositions of orchestral-like complexity and stunning stylistic variety. Bensusan also wrote The Guitar Book to illuminate the concepts behind those records. With his warm baritone voice and trademark scatting, Bensusan is also an accomplished singer. Unlike previous releases, his latest album, Vividly, is split evenly between instrumentals and pieces with vocals. But the recording has plenty to offer the guitar aficionado, including cluster chord voicings, unusual chord progressions, shimmering harp-style harmonics, and dense counterpoint. We recently spoke with Bensusan about his influences, his short-lived foray into electronic effects, and more. What were your formative musical experiences like? I was 11 years old when I first got a guitar and mostly strummed it, accompanying myself singing French tunes and American folk songs. Then, when I heard the music of players like Bert Jansch and John Renbourn, that really gave me a kick in the pants and stimulated me to learn how to fingerpick and play solo, in a contrapuntal style. How’d you get into using DADGAD tuning, and what was it about it that moved you so deeply? Early on, I discovered a lot of alternate tunings by just randomly playing around with my tuning pegs. After a while, I come to the conclusion that I had to stick to one tuning and learn the fretboard in it. I chose DADGAD for its versatility and have been using it exclusively since 1978. [Ed.: In a rare deviation, Bensusan uses standard on his composition “Altiplanos.”] DADGAD is a flattering tuning, which means that you can remain at the surface of it and have an exciting time for a little while. But if you just play a lot of open-string voicings and don’t really investigate the tuning’s full potential, then you are going to sound just like everyone else. So I went about studying DADGAD carefully, playing around with many different scale and chord patterns, many different ideas and styles. After doing this a while, I was able to freely express myself in the tuning. Then DADGAD became invisible: I was playing the tuning—it wasn’t playing me. Tell us a little about the Lowden that has long been your main guitar. In 1978, when I was touring Northern Ireland, I met a friend of George Lowden. Several months later, I saw a Lowden guitar in a shop in Paris, and I immediately fell in love with both the sound and look of the instrument. So I called the luthier immediately and asked him to make me a guitar with mahogany back and sides and a cedar top. I’ve played that guitar, which I call “Old Lady” [Ed.: It is officially known as the model S22], for almost 33 years now and have used it on all of my records. I also have another Lowden, my “New Lady,” which is about three years old and is my signature model. It has a spruce top and rosewood body, giving it a different sound than my original Lowden. It’s very responsive, has a lot of headroom, and is very clear and bright. What’s amazing about the newer guitar is it can be so fast and effortless that you really have to pay attention to what you play so things don’t get out of control. It forces me to approach things carefully, which is good. In what way do you feel like the new guitar can contribute to things getting “out of control”? If you aim right, that instrument gives you a 3-D rendition, close to perfection, but if you don’t pay attention, you can get overwhelmed by the strength of projection. I am grateful that I have to pay that attention to how I touch it, which is the way it should be, and can only help me to become a better player. How would you describe your compositional process? I let my imagination play its role and then allow the guitar to take over. At the beginning, a new piece is just an idea that I have. Over several weeks or several months or several years, I’ll start to incorporate my fingers without ever losing sight of the original concept. Technique can distort an idea, and I’m vigilant about watching out for that. In a way, composing has strengthened my instrumental technique—figuring out how to accurately express something on the guitar has greatly improved my knowledge of the fretboard and my touch on the instrument. So in the beginning a new piece is only in your head? Very often, it is completely and only in my head and has nothing to do with the guitar. I like it to stay that way until I feel the time is right to give it an actual sonic form with what I have in my hands—a guitar—without losing the content to comfort zones dictated by my instrumental technique. Of course, I also find lots of inspiration just by wandering on the instrument. So, it’s a combination of both—imagination and talking with the guitar, looking for the right notes. Your style is all over the map. Can you pinpoint some of your influences? Oh, they’re so varied. It can go from Arabic music—I was born in North Africa—to Celtic music and songs from central France, Brazil, India, Cuba, Mali, and beyond. I’m a sponge and am constantly listening to a lot of different things. But at the end of the day, I’m trying to put all these different sounds—which I’ve learned not by studying techniques and theory, but through osmosis—through my own filter to see what comes out. My music is also influenced by my life today and the world in which we live, which is not the perfect place. And thanks to music, for the last 40 years I’ve been very fortunate to have traveled all over world, experiencing a lot of different cultures and geography. This has definitely informed my music as well. You sometimes scat sing in the manner of George Benson. How did you get into that? When I first heard [Brazilian singer-songwriter] Milton Nascimento, it occurred to me that he was not only a great singer but a painter who creates beautiful moods with the color of his voice, and that inspired me to augment my guitar playing with my voice. At the same time, I got into scatting through George Benson, and later I was influenced by the amazing things Bobby McFerrin does with his voice. But I’ve tried to scat and sing in my own way—what’s the point of copying? In the 1980s, you turned to effects to create lush acoustic-electric soundscapes, but it seems that lately you’ve all but abandoned electronics. Why is that? I was reluctant to enter that world to start with, but once I did I went all the way. I was like a child in a toy store. It was amazing to discover ping-pong delays, to be able to record more than a minute of myself playing, then add layers and layers on top of that. I did sound-on-sound effects live onstage for 15 years, and my music reached a very inspiring place—though I know that some people weren’t happy with my experiments. Using effects, I felt powerful, but that ended up being a very dangerous thing. I started to feel as if I couldn’t function without effects—and that freaked me out. So, one day before a new tour began, I took a look at all my equipment and said to it, “You stay here— I’m going without you.” I left for the tour with only my guitar and a cable, wanting to touch people with just the instrument. At first, it was difficult to be stripped of effects. The guitar sounded so small, and on some sound systems, not so great. But I started to accept those sonic limitations and work within that dimension. I concentrated on things like making a beautiful vibrato tell a story, and after a while I got to a point where I could do a concert with no PA—just a guitar and a room. Now I bring a minimum of equipment on tour— my guitar, a volume pedal, a reverb unit, two microphones, a little guitar stand, a music stand for the lyrics so I don’t forget them. And that’s it, except for an electric fan to keep me cool—and that takes up the most space of all. Has ditching effects changed your playing at all? Yes. Effects, especially reverb, can greatly mask the sound of a guitar and cause you to forget its natural sound. When you just play a naked guitar, you’re confronted by the pure tone and understand that it requires a lot of work and attention to make the instrument sound beautiful. When I stopped using effects, I found myself concentrating a lot on my right-hand attack and on my left-hand touch. I was forced to address the sound correctly on an acoustic level, and that’s why these days I record without headphones and maybe add just a tiny bit of effects later in the recording process. Tell us a little about your latest album, Vividly. On the last recording [2001’s Intuite], I put my singing aside. But this time I wanted to do a record where songs with lyrics and instrumentals shared the space equally. I tried to create a sequence of tunes that would make sense as a whole and would also make sense if you listen separately to the songs and the instrumentals. For each of the songs—some of which I was happy to collaborate on with my wife, Doatea, and a singer-songwriter friend from Los Angeles named Nina Swan—I was careful to record parts that didn’t conflict with the lyrics. I wanted a listener to be able to pay attention to one element at a time without any confusion. In other words, I treated the voice and guitar like equal instruments. I’m very happy with Vividly, which some people have told me is my best record to date. My guitar tone has improved. I sing better than I did in the past. Most importantly, it’s a record that shows where I am as a musician and as a person. Improvisation seems to play a real prominent role in your music. I try to be as spontaneous as possible by approaching a new composition with the notion that it’ll never really be completed. I’ll of course try to learn what I’ve written note-for-note, but very soon after that I will deviate from the piece and play it more freely, giving myself a bit of a vocabulary around the places that my fingers know. I’ll follow a piece to where it leads me. Here’s another way I look at improvisation: At the end of the day, everything we learn on our instrument has to be forgotten, because as much as you work hard to overcome the technical challenges that surface when you approach music, ultimately you need to ignore all that information in order to be fully attentive and reactive to what you are instantly composing. What makes for a strong improviser? It helps to have a thorough knowledge of the fretboard, to know the different locations of any given chord and its inversions, to have multiple positions for scales and modes under your fingers. At a certain point, though, you have to stop thinking about scales and actually play music. Music is much more than just a logical and harmonious juxtaposition of melodies. Inside all this, there is an intact abstraction— a brutal and vibrant jewel—calling for your senses, emotions, and all our human feelings. No words can describe that sensation. If there were, then there would be no need to play or listen to music anymore. 附:Pierre Bensusan's 的装备: Guitars 1978 Lowden S-22 (dubbed “Old Lady”), Lowden Pierre Bensusan signature model (dubbed “New Lady”), signature Altiplanos archtop made by Michael Greenfield, Juan Miguel Carmona nylon-string, Kevin Ryan steel-string Effects Ernie Ball Volume Pedal, Zoom H4 handheld digital recorder (for reverb) Amplification Headway Pickups piezo pickup routed through Fishman internal preamp (60 percent of the signal), custom mic handmade in Michigan (40 percent of the signal), RØDE vocal mic Strings and Picks Wyres .013–.056 signature set, clear Dobro thumbpick |